On coat of arms: design to negociate with belonging and tiny mythologies

Workshop

On the occasion of the yearly festival Feral by Cifas this year on the theme of the middle-age, OSP was invited to make a workshop around Coat of arms. We decided to make this workshop part of the plotterstation (more information on pen-plotters here). The workshop was presented as

... a practical workshop on creating and making coats of arms on fabric. Using a database of medieval coats of arms from Belgian municipalities, we will remix or redesign these heraldic symbols to give them new meanings. These coats of arms will be drawn on fabric using a pen plotter (a mechanical drawing tool that uses “traditional” pens) and will be turned into badges, vests, T-shirts, patches, etc.

The workshop took places over two afternoons, from 2:30 p.m. to 5:00 p.m. each day with a different audience. This idea of a middle-age was unfolded through various other workshops: ointments making, shifting perspective through body practices, making kin outside of nuclear familly through roleplay. Then also talks... on the idea of new commons by Simona Denicolai, a trans or queer middle-age by Clovis Maillet, and The middle-age as a Myth by the historian and writer Pierre-Olivier Dittmar.

In the midst of this, our coat of arms workshop was meant to think together by drawing together and to produce new common symbols as tool for thinking (even if akward, naive or subjective). The workshop happened in the beautiful library space of Mona, an old monastere now used a space for artist and housing for people, handled by Toestand. The picture of the workshops are under © by Asma Laajimi.

To belong

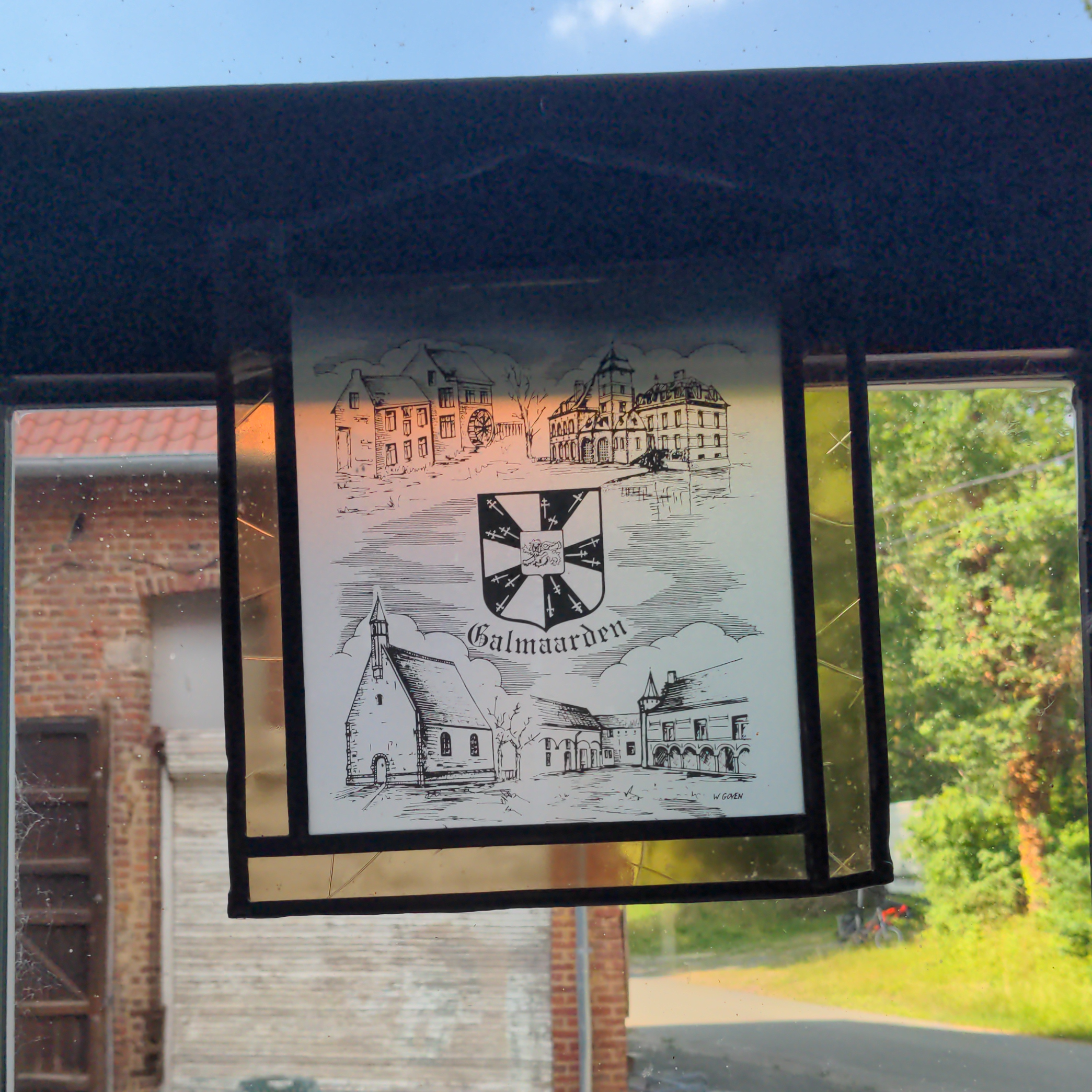

Today lots of people love to upcycle middle-age aesthetics for many contexts (from contemporary artists, to queer communities, to right wing propaganda, etc), but that left us with a more serious questions about coat of arms... outside of their appealing graphics what do they actually mean and what room do they leave for re-interpretation? If we want to reappropriate those shapes we need to know their origins. We realized their still present in modern documents: you can find them online on the websites of belgian communes, or on street signs for example, but also on cops uniforms...

Without pretending to be middle-age experts, we tried to situate coat of arms through a few point of history. In every cases, coat of arms are symbols of "belonging". Firstly even before the middle-age to recognize the different fighters in a battle, hence the shield shape that stayed through time, it was a figth belonging, started with the Gaulois. It spread with the crusade as propaganda and colonial claim, generalized to banner, helmet and other supports. Then this war-like belonging transfered with time to be a labour and land belonging with feudalism, outside of any battlefield, through the middle-age.

Broadly defined, it was a way of structuring society around relationships derived from the holding of land in exchange for service or labour. (Feudalism on Wikipedia)

In the context of feudalism, to belong is about opportunistic alliances. It is an economy: you work the land of the lord as a peasant (serfs) in exchange for food and protection by the vassals (knights). They were also guild coat of arms, to show your belonging to a field of practices, or ecclesiastic a spiritual belonging. Then coat of arms faded-out for a bit, and later during the XIXth century, regions and province re-discover their heraldry to express "the identiy and autority of a territory against state interventionism" (sentence taken from wikipedia). During the XXth century noble familly inherited from this heraldry and transfered it through generation with modifications.

So it's an iconography that also talks about nationalism, colonialism, power and we don't want to hide that darker part, or romanticise it's aesthetics. Yet communes reclaiming their coat of arms can be seem with a little stretch as an anarchist thing: to emancipate our symbol from the authority of a state and to reclaim our local history. Pour retrouver ce qui fait la spécificité d'un lieu et venir se détacher de la mainmise de l'État ? Secondly, to belong doesn't mean to have shared moral values, to have affinity, to be a completly united collectivity, let alone friendship! but more as a non-idealized untanglement between your life and other life in order to continue to live.

We find ourselve conflicted between the need and right to belong, while refusing to entierly conform (re-written ideas from a Judith Butler talk in Gent 2025)

This idea of "frictionnal belonging" find itself at the center of many very modern questions... to what do we belong today? In a recent talk in Gent 2025, Judith Butler mentionned the paradox between belonging being a right that everyone should have access to, think about immigration and the right to be recognized as citizens, or transidentity and the right to be belong to a gender, or even the right to be part of institution or field of practices and question of powers and representations. While at the same time to entierly belong to something means to fade out from any criticality or individuality: it means to conform. So we have to navigate between the "forbidding people to belong" and the "entierly belonging and thus conforming", because both side are fascist tools. Can the exercice of collective coat of arms making help us to negociate with the paradoxical nature of belonging?

Tiny mythologies

Increasingly, the period is seen as a set of positions proposing solutions from a pre-capitalist world for organising our future, our survival. But the same period is now also being used by far right groups to further their agenda. The new Middle Ages are at the crossroads of these struggles, and we need to know more about them if we are to understand what is happening to us. (Cifas introducing the work of historian and writer Pierre-Olivier Dittmar)

It's true that the middle-age is today a set of myths. That is to say a fabulated past where we can project our modern stories to made them say what we want. We bend it to lead to entierly different interpretations. In modern pop culture it is both re-used to support fascist conservative ideology and feminist and ecological re-interpretations. Between Harry potter, Games of Thrones, Feminist witches, or memes that take back middle-age aesthetics. Pierre-Olivier Dittmar supposes that we used to do that with the Antiquity and that we need a gap of something like 1500 years in order for an era to be far enough to become a new myth. But all those reinterpretation shouldn't hide the more difficult origin of such symbols.

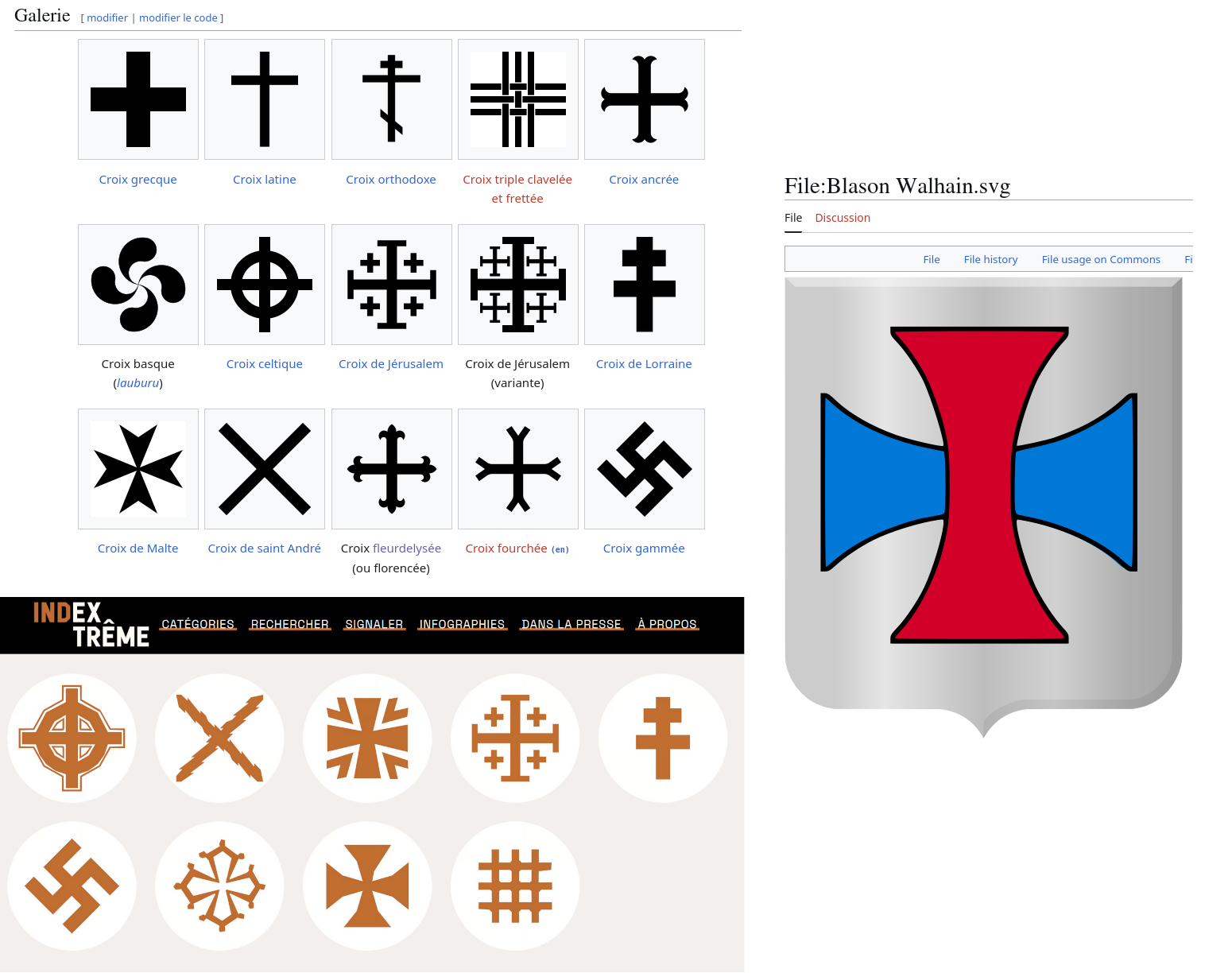

During our selection and research on coat of arms, we browsed the list of meubles on wikipedia (meubles are the name of the individual often figurative symbols sticked on coat of arms), and compared some of them with the symbols present on indextreme, a french website that list fascist symbols usage. The indextreme website brings precisions about the context of uses, like by who, when, for what. They also have the following quote that feels really appropriate.

“The power of a symbol lies in its ability to produce meaning and communicate that meaning.”

Indextrême is a tool designed to understand, in the French context, the symbols used and misused by the far right. By learning about their history, we can better understand the semiotic mechanisms of these symbols and their impact on our society.

What interest us, is how symbols can be used to gather, to make commons, outside of idealized smoothed out commununities, but if we do so which myths are we taking with us and which myths are we leaving behind. In our times, it seems we lost any "grand narrative", we don't have one lord anymore, we don't have a all emcompassing spirituallity anymore, and are left with "tiny mythology" - we navigate contradiction, we belong to many identities that we carry with us. Can the making of coat of arms be a tools to explore those tiny mythologies, the one we are against as well as the ones we incarnate?

During the workshop we asked every participants to what they belong today.

We mentionned the techno-feudal interpretation of Yanis Varoufakis: Where we users of big tech services (amazon, google, apple, meta, openAI, ...) - and the idea that everything is becoming a "service" we depend upon - are working by generating more data and thus more economic value for the tech lords. Yet we have created dependencies relationship with those technology and have become untangled in them.

A more optimistic one maybe is the one of the new commons, for example Simona Denicolai discussed with Toestand during the festival about shared and collectivelly owned building. Or as artist-worker in Belgium we might think of cooperative like SMART, that grant us some worker-rights in exchange for a pourcentage of what we get. But not all of those belonging have to be from a corporation or an association or a cooperation, we can also think about a colocation! Where we are often balancing the rent of a room, the comfort and situation of the space, and our social links with the other roomate all together. We also poeticaly evoked how "With the dispossession of our localities our only territories are ideological".

The rounds of conversations included a lot of other tiny mythologies: collective hospitality or shelter, the access to joy, fight and activism, shared neighboorhood gardenning, veganism, queer communities, where we come from, more-than-human alliances, sharing services normally provided for a familly with chosen people, bikinf or walking communities, collectivising the machines used for artistic production like a printing press or movie making tools, people with pets or animals in the city, the right to slow down or the right to quietness, avoiding mainstream social media.

Declarativeness

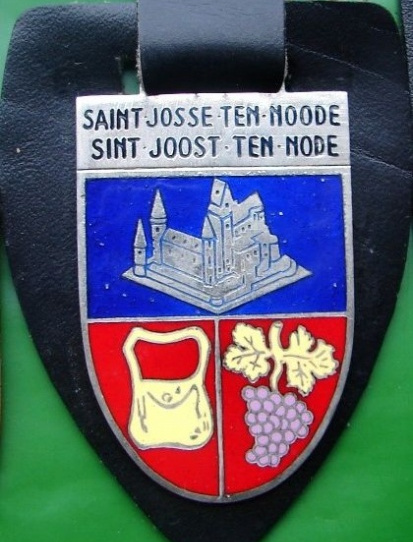

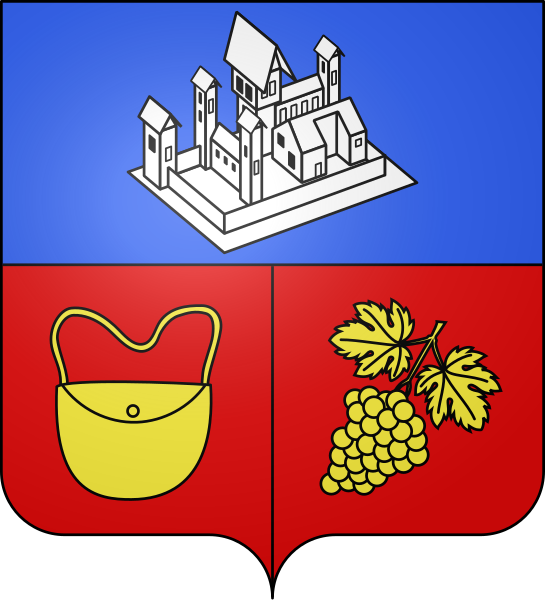

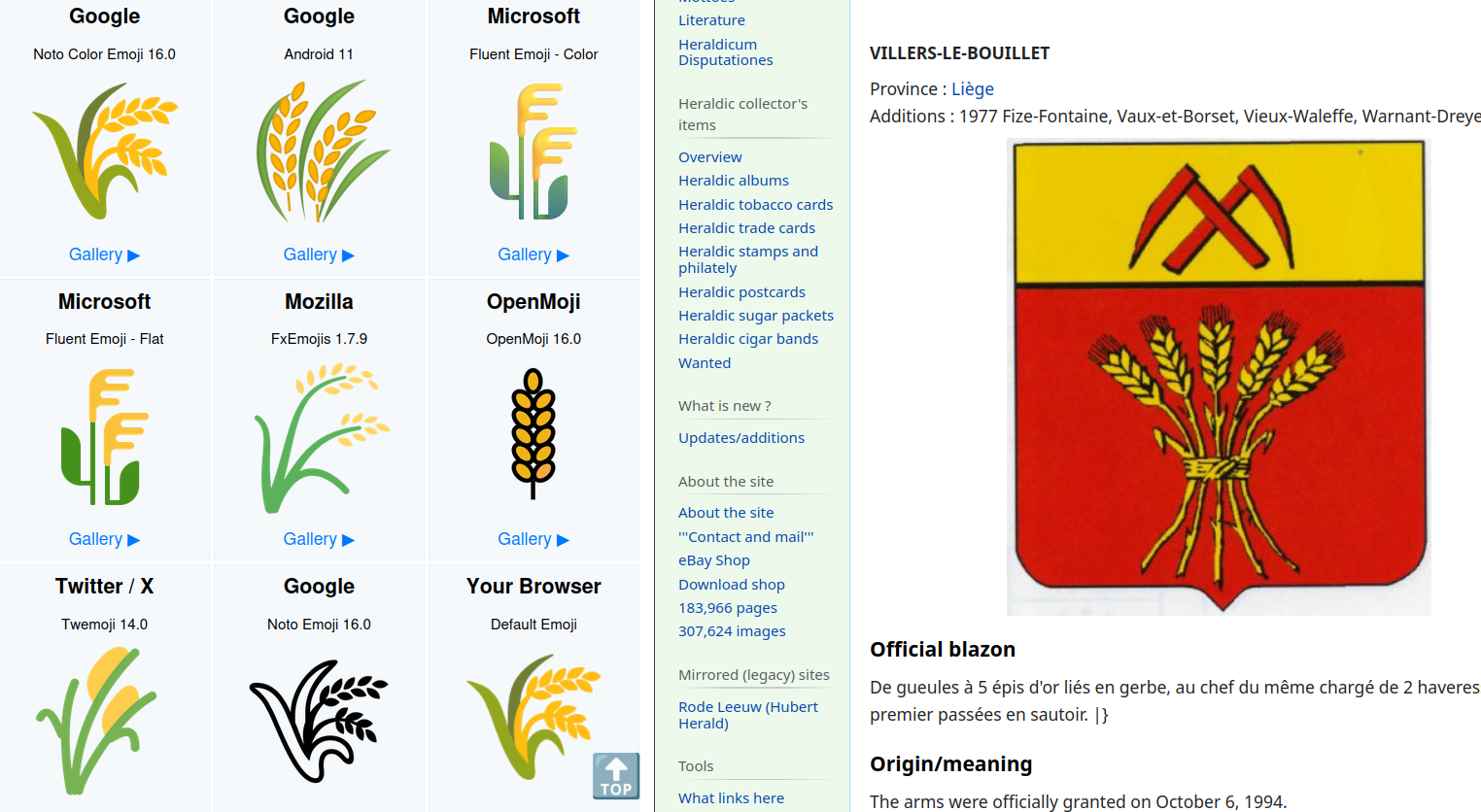

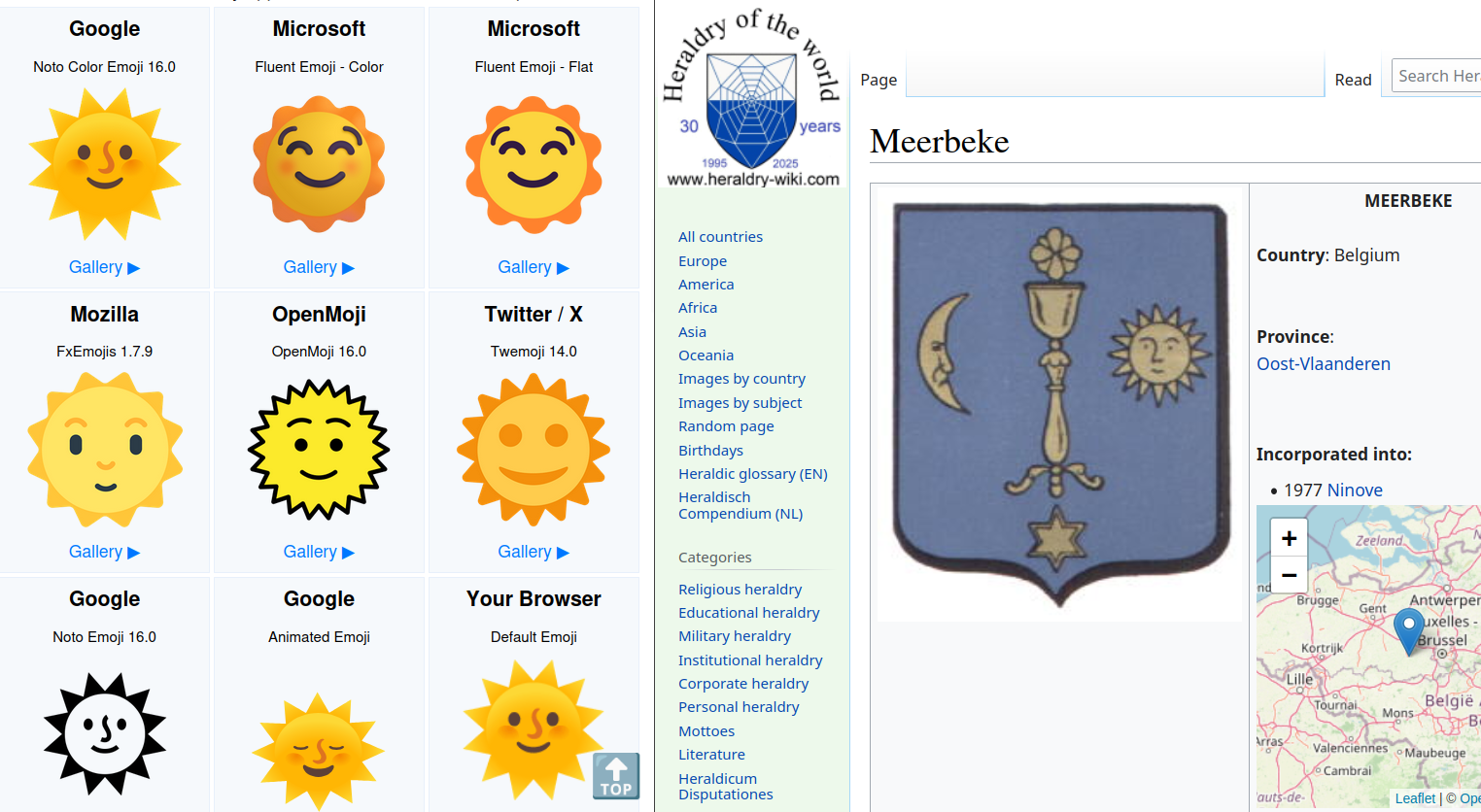

In order to present our full interest in Coat of arms we have to talk a bit about language as a materiality. See, coat of arms often have many version of themselves and there isn't one that is the official version. Also alongside all their visual representation exist a small text, in old French with a very particular syntax. The words, syntax, grammar of those coat of arms "declarations" are actually very precise and constitute a craft in itself. For example there is a specific palette of 6 colors and 2 metals. But also a bunch of word to describe the layout division, or the patterns, or the position of meubles, etc. Tthe design of the coat of arms of a city changed through the centuries, but even at one given moment there wasn't one version that is most original or official, they all are with, and their differences are somehow allowed in the design. And this fluidity of interpretation is allowed ecause their primary materiality is language. To get a sense of the variations let's look at a collection of coat of arms from 5 Belgian commune, alongside their original text.

|

|

|

|

Saint-Josse Coupé d'azur à un château d'argent, et d'un parti de gueules à une besace d'or, et du troisième à une grappe de raisins tigée et feuillée d'or. |

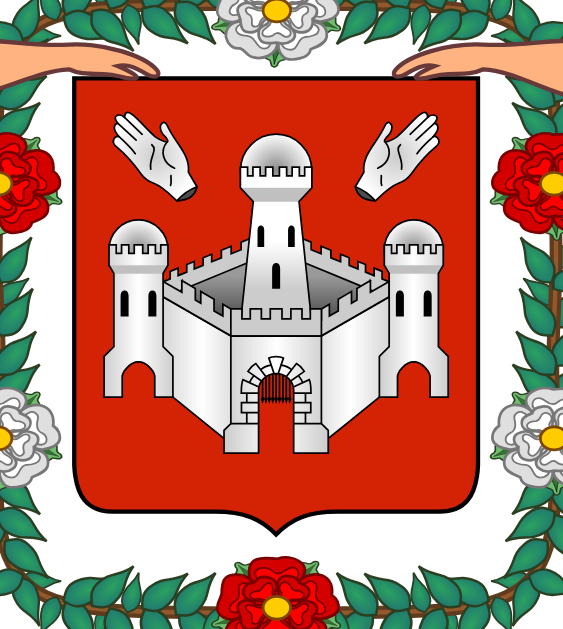

|

|

|

|

Anvers De gueules au château de trois tours d'argent, celle du milieu crénelée de cinq pièces, ouvert, ajouré et maçonné de sable, surmonté de deux mains appaumées, celle à dextre en bande, celle à senestre en barre d'argent. |

|

|

|

|

Ixelles D'argent à un aune au naturel. |

|

|

|

|

Watermaal Boisfort D'argent à une rencontre de cerf au naturel, au chef d'azur chargé d'un cor de chasse d'or lié du même. |

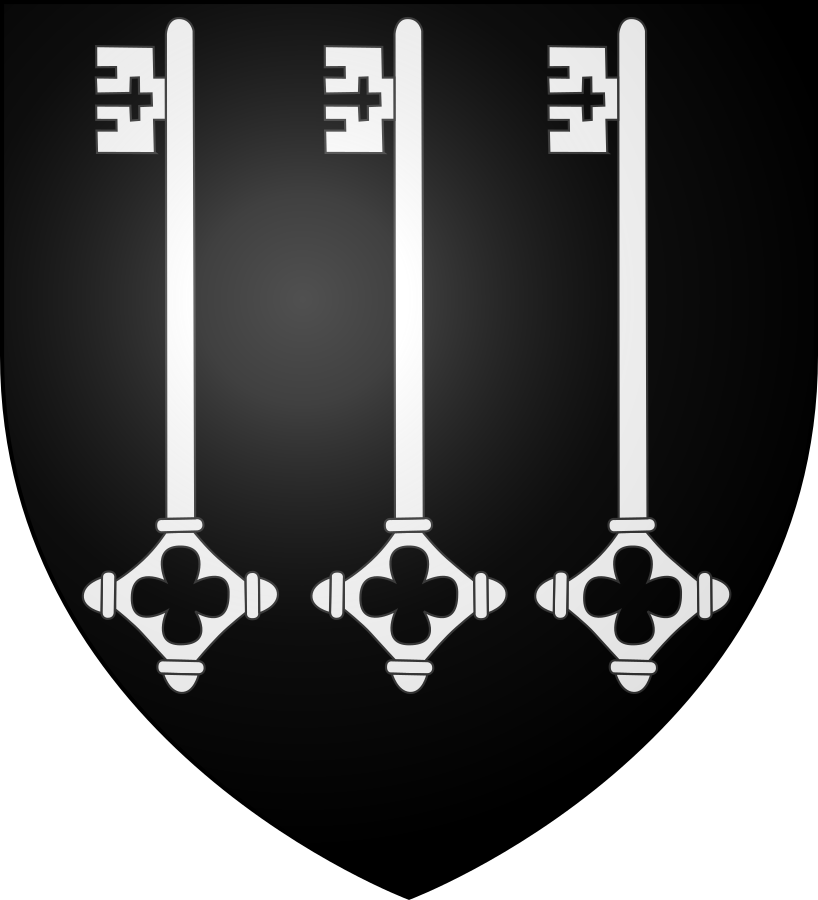

|

|

|

|

Gembloux De sable, à trois clefs d'argent, posées en pal. L'écu sommé de la couronne de comte ancienne à treize perles. |

It make sense to ask why, right? Well in the middle-age we can't send a vector file or a jpg over the internet so that the artisans can replicate the design. We needed some form of lightweight encoding that can be reinterpreted by different crafts, so the artisan of the city can translate it to different materials, like on a textile banner or a metal shield, either by drawing, carving, embroiding, ... while maintaining some intentions through the different instances of the design.

As digital designers we recognised this declarative approach to design from another more recent medium that is the web. Web languages like HTML and CSS are said to be declaratives, when "coding" ("declaring") a website we declare which display mode is going to be used in each container using keywords like block, inline, flex or grid. We position element through kewywords like relative, absolute, sticky or fixed. Some colors have specific names like "orangered" or "palegoldenrod". This means that websites, just like coat of arms, can lead to different rendering through different devices (from different period of time, of or different sizes, like a desktop computer, a smartphone but also a watch, a ebook reader, or a web document printed on paper, etc). Through the artistic research Declarations artists explore the ambiguous visual-textual materiality of declarative design (mostly on the web, though it takes many shapes and crafts outside of the screens).

_page_193.jpg)

if we're going to allow multiple devices with different graphic abilities to display the same web, then we have to give up control of fonts and colors and display properties. So right grom the beginning, there's a problem with design on the web. It's problematic to design in a way that's going to be device agnostic. [...] that's why CSS is a declarative language. That means that rather than describing, as we might in JavaScript, the steps to take to recreate a specific outcome, I instead describe the intent of my outcome. What am I going for? What am I pushing towards? And I'm trying to give the browser as much meaningful information as possible, subtext and implications, ... CSS is more linguistical than logical. [...] CSS is contextual: we can make suggestion but we can't insist on the final design. And have to embrace the fluidity as a feature, rather than a limitation. (Miriam Suzanne from her super good video Why Is CSS So Weird? 2020)

Back to the context of coat of arms, we could argue that the declarativeness of their design makes perfect sense: they also need to be context agnostic while embedding specific intentions. But rather than just prompting a description intuitivelly out the void like one would do to an AI model... both CSS or Heraldry are their own language. Thet have a well-defined grammar, an ambiguous visual-linguistal syntax, their own world of shapes with finite combinations, yet infinite fluidity. What we love about those is that by providing a language they also provide a context for thinking, a type of situadness.

Wikipedia & Open Moji

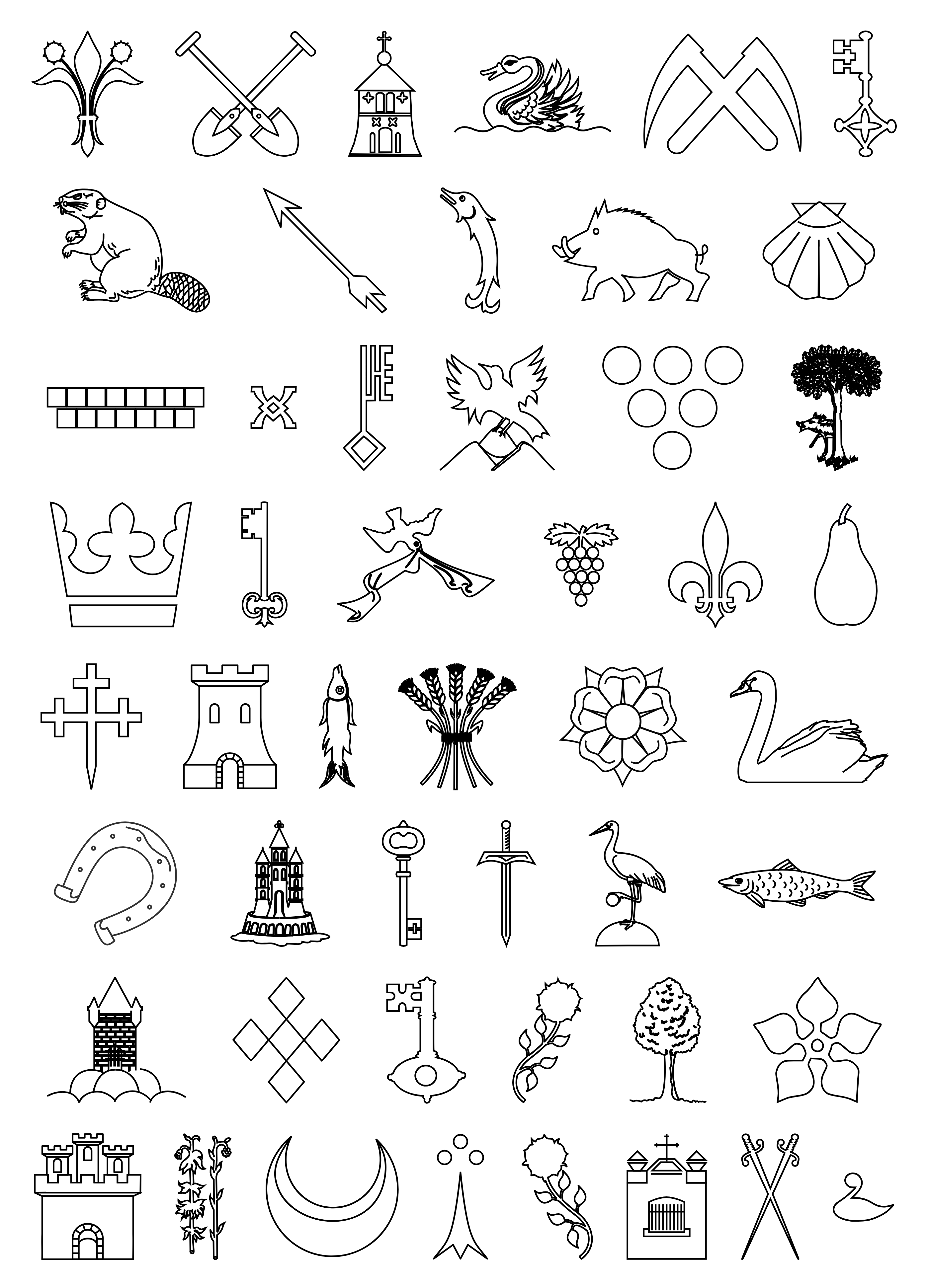

In order to re-interpret symbols during the workshop we need some material to start with! Since coats of arms are often mentionned on the Wikipedia pages, many exist as vector drawings under a free license, made by contributors. We used a script to download all the vector coats of arms of Belgian municipalities, and then manually extract shapes and designs based of our visual interest or symbolism curiosity. Here's the category SVG coats of arms of municipalities of Belgium on Wikipedia, from that we gathered around 180 simple outlined vector drawing.

We naturally came to categorise the meubles - like a snake, a tree, a sword, a geometric shape - into categories. Often categories are like animals, plants, geometric shapes, human body parts, etc; which ressemble a lot to another category system we are used to see: emojis. And just like during the middle-age two artisans aren't going to draw the same key on a coat of arms, the key emoji can appear through different shapes depending on the software you use. What's interesting is to ask what made certain symbols part of either heraldry or emoji "dictionnary", like when they are not just a drawing, but a shape that was repeated enough so that it is a culturally anchored symbol?

What an emoji is in fact, is a symbol validated by the Unicode Consortium, just like the latin alphabet or a punctuation sign. The Unicode Consortium doesn't really fix the visual representation, which depend on the typography used. Just like they are many ways to draw the letter S, in script, serif, sans-serif, monospace, they are different visual interpretation of the following emojis ⚙️ 🌱 💫. Often the fonts used to render emoji will depends on the operating system or software you're using. Also their linguistical meaning have been shown to evolves over time and with usage, simply think of the erotic interpretation of 🍆 or ✂️, or the most recent uses of 🍉. We tried to see if some of the symbol that we send to each other over the internet as emoji are old enough to appear in certain coat of arms, and surely...

We expanded our collection of 180 vector shapes from Belgian coat of arms by adding all the non-smiley emoji from the font OpenMoji an open-source and non-big-tech-owned emoji font. Despite not being the emoji representation we are the most familiar with, this font has the advantage of being both accessible in color or black outline version, just like our coat of arms shapes from Wikipedia.

At the start of the workshop, during the presentation tour of every participants, we asked everyone (additionnally to their name and pronouns) to tell a little something about their use of emojis: a favorite one, a hated one, a most used one? The quick collective portrait that this simple exercice created was already rich in visual stories: a pear, a red pointed heart, a beaver, a double chain-link, a reversed smile, some droplet of waters, a mouth biting their lips, etc.

Design as negociations

From those rich exchanges on emoji and belonging, we splitted the group in 3 subgroups of interlaced topics. We had printed a small zine with our collection of both vector shapes from coat of arms and openmoji characters. Together we started browsing the selection of shapes while discussing. We selected what intuitivelly called us, and try to explain it to each others. Drafting and sketching ideas on collective big sheet of paper. This process of co-designing outloud is fundamental to activate ideas of common belonging. It is not at all the same thing than asking one single designer to make a logo. For example if we have to make a coat of arms for the idea of "shelter" we have to negociate between many point of vues on what a shelter actually is in order to find back some common symbolism that brings us together.

In that sense the design process is both about making the coat of arms, than about finding out how and where we meet and where it's complex. It is an explorative process, and it is difficult. Mainly because it requieres social skills that are often forgotten when talking about design... in oppoistion with the often idealized loneliness of the designer behind a computer in control of everything. It ask us to navigating complex conversations, shifting point of vues, seeing where the group dynamic tends to go, situating ourselves, giving up part of the control, or finding joy in ambiguity and multiplicity.

Because of the short amount of time for the workshop and our desire to end up with physical plotted textile object, we didn't went into the exercice of properly declaring our design but would have loved to do so.

Making meaning

Here we present, as they are, the outcomes of the workshop in all their multiplicity of negociated belonging (and sometimes much appreciated sillyness).

This one was a negociation on the themes of veganism, nature, anti-specism, more-than-human, need for earth ressources. At the center a cycle of animals and plants representing ecosystems, with on its side an empty triangle for the paradox of every representation of nature being done from a human point-of-view. Below the lands, and the human relationship to land claiming it for farming vegetable (here a radish) and the idea of feeding deliciousness and desire represented by the mouth biting their lips. On top, a hand giving a flower bouquet as a burning heart, the passion and violent wilderness of it all. All contained in a droplet of water, shining as a sun.

This one was a negociation on the themes of collocation, collective life, putting ressources in common, opportunistic alliance under capitalism. At the center a double-loop, because when living in collective we always go through recuring difficulties but always ends-up a bit further. Inside of the first loop there are plants for the ressources and tools in the second one for the work. Below two hands sharing the same key. Above a fox next to a tree, symbol of gathering ressources in sneaky or tactical ways and bringing them to the rest of the group. The usual shape of a shield as been inverted to evoke the one of an entrance.

This one was a negociation on the themes of the necessity of hospitality, the privatisation of land, the right to belong to some place. Many version where made, here's two of them. The first one is made of plants growing in a wall, reminding us that there are always a possibility of making it in unwelcoming structure may them be spatial or legal. The shield shape was also inverted to become an entrance, the plants even outgrow that entrance. The second one depict a burning ID card, next to a migratory bird and a comfy couch.

This one was a negociation on the themes of artist-workers social right, mutualisation of machines and spaces, cultural cooperative and money and materiality in our practices. The beaver became a good symbol for artists as they both make bridges and block or slow-down flows. One beaver is holding the idea of machines needed for artistic production, the other is holding a growing plant for the learning of practices and ideas, they're sharing it to one another. Above, an inverted crown of tower for the underground constellations made of the many shared art studio of a city, and what bounds us through our respective practices. On top, fire to both represent the burning world and an endless motivation.

This one was a negociation on the themes of the importance of joy and shelter, spaces to feel good in, what brings us together and care. [... to complete by vinciane]

This one was a negociation on the themes of slowness and how we can afford slowness, biking, walking, or animal presences in our lives. [... to complete by sarah]